It rained and rained all night and most of the next day, drenching the millions of pilgrims who had gathered on this cold winter day at the Kumbh Mela. All the planning and arrangements broke down. Crowds of people were slipping in the mud. Ambulances were stuck and could not reach the disabled. New problems arose that no one had even imagined. Thousands of families were separated. I saw a desperate woman whose three children were lost. Later, I saw a small child, barely four years old, lost, dazed, and trudging through calf-deep, slippery slush.

All the suffering confirmed my revulsion for religion.

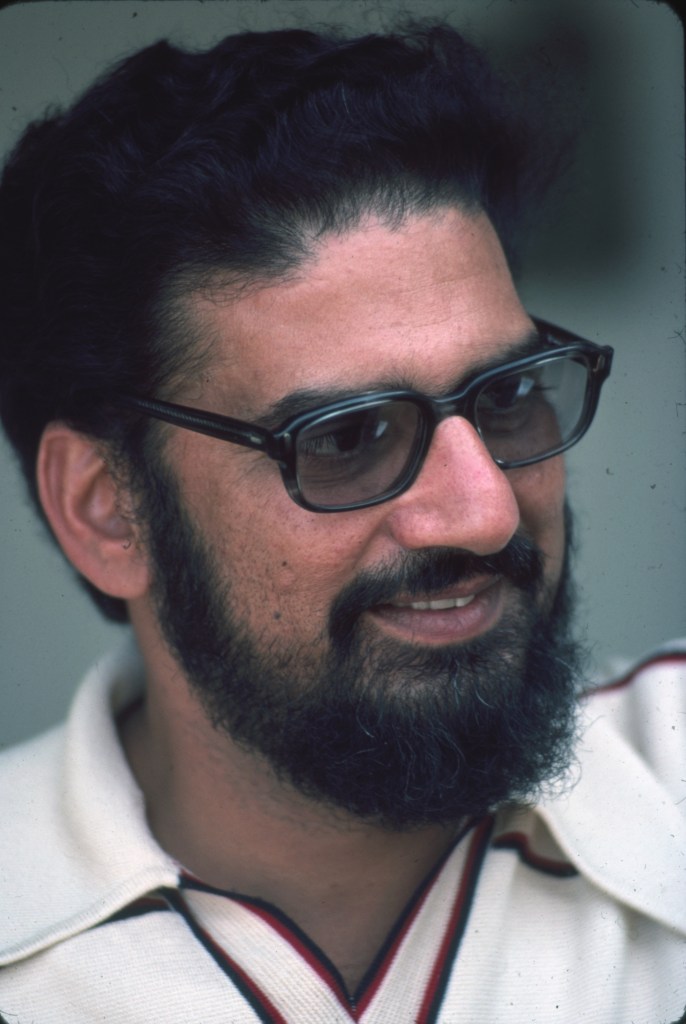

That afternoon, I interviewed an itinerant barber. He and his customer were squatting in the slush, drenched. With his tools beside him in a tin pail, he was oblivious to the commotion around him, doing his job of shaving pilgrims’ heads for one or two rupees.

“How much money had you expected to earn today?” I inquired. He told me he had expected to earn 125 rupees, but because of the rain he had earned only about 20 rupees. For a poor barber like him, it must have been a financial disaster.

“Did God do good or bad by sending this rain today?” I inquired condescendingly.

Without missing a beat or even looking at me, he patiently answered that rain was simply a happening. “We can choose what we wish to perceive in it,” he said. “Could we, with our limited perception, judge an act of God? Everything in the overall perspective happens for the best, even though it may not be evident to us at that time.”

The words of that barber were neither new to me nor very profound, but their impact on me was stunning. I stood there, speechless.

I grew up with the understanding that everything happens for the best. It was something I believed. It was an “article of faith” for a little child, just like knowing the sun will rise or that my mother loved me. It was not based on any intellectual understanding. It just was.

But later, during the partition of 1947, when British India was divided into the two independent states of India and Pakistan, hundreds of thousands of people were killed—all in the name of God. That horrible experience did not match my belief that everything happens for the best. How could killing in the name of God be good? How could injustices, cruelties, or crimes be good?

I concluded that the belief that everything happens for the best must be an “opiate of the masses.” As long as such notions persisted, there was no hope for human beings. As I started to explore my horizons, I could not find any intellectual support for my childhood belief.

Now, after this one statement by that barber, I stood frozen, transfixed. I felt like any movement on my part would bring attention to my utter nakedness. It was as if something within me had been whittled down over time, and with the barber’s statement, it broke. After a few moments, I slowly moved on. The barber did not glance at me nor utter another word.

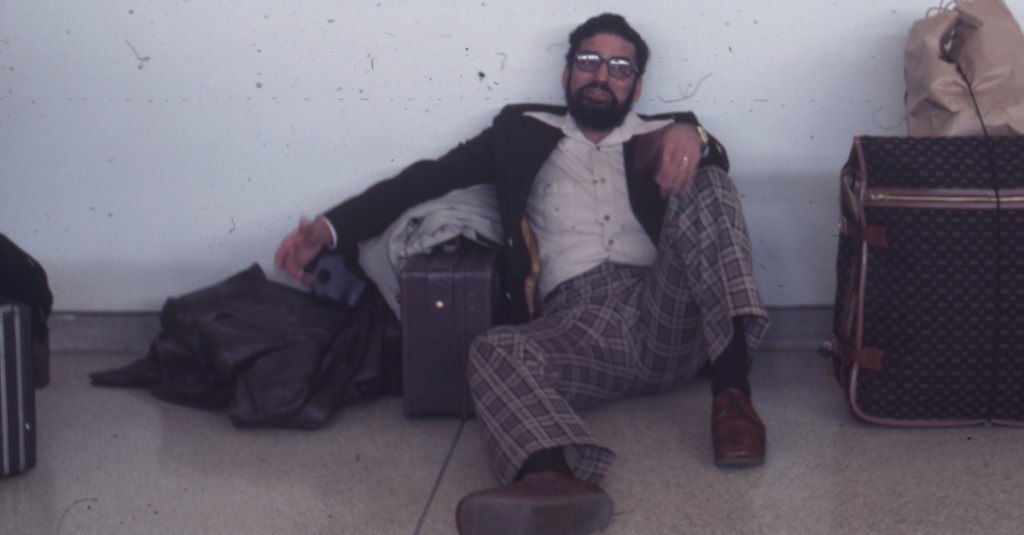

Soon after that, I left for New Delhi on my way back to the USA. I spent a couple days in Delhi with my aunt and uncle.

The night before I was to depart from New Delhi, I went to bed early so I could get up and catch my 4 a.m. flight. After only two or three hours of sleep, I awoke and found myself engulfed in a powerful, yet subtle feeling, a beautiful ambiance. There was something familiar about it. And then, in my half-awake, half-asleep state, the flower appeared.

In my memory, I was transported back to when I was six years old, and my family was on vacation in the mountains. As I was walking down a narrow trail one day, I bent over to admire a tiny flower. From a distance, the flower looked solid blue. But when I looked closer, it was an amalgamation of several shades of blue, intermingling in a joyful mood—and I could see tiny veins in its petals. I stood there in awe, enchanted.

Then, with the innocence and tenderness available only to the very young at unguarded moments, I asked, “Can you tell me the meaning of life?” I spoke to the flower as if I were talking to a newborn baby. I dared not touch the tiny miracle in front of me, for fear of hurting it. The wonder I beheld was precious, priceless.

Perhaps, as a little child, I identified with that little flower. Because at that moment, I realized my own smallness and vulnerability. For a child who had been coddled as if he were the center of the universe, one would think such an experience would be disconcerting, or even threatening. The effect was quite different.

I remember a gentle feeling dawning upon me, a feeling of lightness. I recall walking home with a big smile, as if I were walking on clouds.

Now I had that same feeling as I lay in bed in New Delhi. In my half-awake state, I could see the beautiful blue intermingling colors of that flower. It was as if the flower had come back to remind me of something. It had not answered my question. But somehow, in that moment I had discovered a slant, a perspective, an approach to life. The flower’s life would be so brief. Each moment was precious, a treasure, a miracle. In that light, how do I respond to this universe? The flower had not told me the meaning of life. It had given me a handle on life.

I thought of the barber at the Kumbh Mela. What was it that allowed him to remain so calm, even though he had suffered such a financial loss? And, it wasn’t just him. It was the crowd of millions of people who had remained calm in the middle of such chaos. What was their secret?

It suddenly struck me—I had focused on all the outer events of the Mela, how it was organized, the masses of people, the food, the bathrooms and so on. But I had missed the central point! I had missed the essence of it. The barber was extremely poor, from a village, with no education and no philosophical training. Yet there was something in him, something deep within the DNA of the culture itself—an unseen treasure. That is what I was supposed to learn, but I had missed it. I had not done my job as a reporter, and I would not be able to do justice to my intended article.

Immediately I got up, canceled my flight, left a note for my uncle and aunt, and caught a train back to Allahabad.

There was no time to waste. I went right to work. I was no longer interested in hobnobbing with the VIPs. This time I wanted to talk with the common people, the ones who had walked countless miles, often barefoot, just to be there and walk on the sands by the Ganges.

I realized that, having grown up with a Western education, I had never known the core values of the common people. As I spoke with them now, I was no longer wearing blue jeans, and I was no longer impatient with them. I interviewed 63 people, by count.

Everyone I spoke with gave me practically the same answer as the barber. Their perspective that everything happens for the best was deeply rooted, a part of their very being. From that simple acceptance of “life as it is” seemed to flow a great strength, peace, and wisdom, a deep understanding of life. Irrespective of their lack of education, their superstition or poverty, they could dance with life. It was not dependent on any outside circumstances.

I was humbled. It became a matter of pride for me that I shared the same primordial DNA as these people.

In fact, I found my own perspective starting to shift. I was no longer seeing the Mela as a journalist. I was there to reconnect to my roots. I was no longer trying to understand it all intellectually. I wanted to experience it. I was like a child who has their first taste of sugar and just wants more and more. I was now a seeker.

Just as quickly as the multitudes of people had appeared for the main bathing day, they left. In a couple of days, only the very dedicated pilgrims remained. They would stay there for most or all of the 40 days of the Mela.

I never even saw the photographer sent by National Geographic. I was told he came on the day of the Mauni Amavasya and left the next day. Because of the rain, his photographs did not meet the standards of National Geographic, and they scrapped the idea of the story before I could even start writing.

When I received the call from the magazine telling me the story wouldn’t run, the only thought going through my mind was, How did that “350-year-old man” know? To the person who called me, I just said, “I understand.” Because now I knew that I had not gone there to write an article after all.

Little did I know that on that rainy day, in the midst of an unforgettable human drama, a humble barber would change my life.