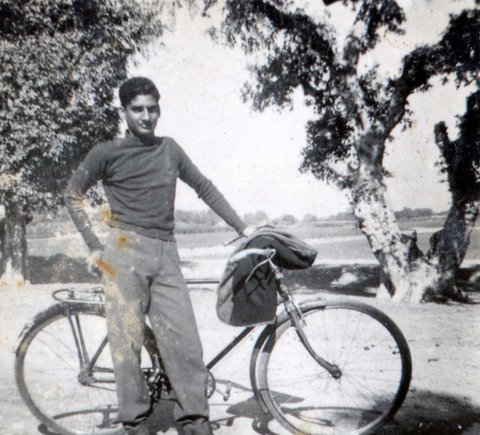

At the age of seven, I received my first bicycle.

My father paid 50 rupees to purchase the bike from a British family that was leaving India to return home to England. In 1942, even 50 rupees was a lot of money. Most bicycles were imported from the UK and cost in excess of 200 rupees, which would have been a year’s salary for a daily laborer.

Since few people could afford bicycles, practically everyone walked—even great distances. Native ekkas (one-horse carriages) were available for hire, but most people did not have money even for that small fare.

All bikes were a standard size and painted black. But my bike was special: it was a small, child-sized bike, and it was shiny light green. I never saw another small bike like that in the whole city. I acquired celebrity status. People would stop in the street to watch me ride, or come to their windows to see me pass by.

As a result, my showmanship blossomed. For me, it was never just a bike ride. It had to be a performance. I would pedal as hard as my legs would permit and catch up with anyone on a bike ahead of me. I would show off how I could ride with no hands, whizzing past all the pedestrians while precariously balancing on my two-wheeler. Or, I would challenge others to a race.

Those must have been safer times. Not only was there very little traffic on the streets, but I could ride for miles out of my neighborhood without causing any concern for my parents. At one point, I even thought of making a map of the city, but I refrained when I realized I would not be able to draw it to scale.

Not long after I got my bike, my father was commissioned as an officer in the Indian Army, which was part of the British Empire. World War II was in full swing, and immediately after his training, my father was packed off to fight the Japanese in Burma.

Several months had passed when, early one morning, we heard a knock on the door. To my surprise and joy, my father was there! He was dressed in his uniform, and his left arm was in a sling. He had been injured, and was flown to a hospital in Calcutta. There he had been given a one-day furlough to visit his family in Allahabad, an overnight journey by train.

Along with him was his orderly, the soldier attendant to an officer. Father told me his attendant would like to take a dip in the holy Ganges and asked me to accompany him. For the Hindu orderly, who came from a small village, this was an opportunity of a lifetime.

The trip to the river and back was almost 10 miles, normally a great distance for a 7-year-old boy—but not when he had his mighty green bike! The orderly was in his army uniform and carried his lathi, a bamboo rod, which in those days was the main weapon for people from rural India. As he walked, I would race ahead on my bike and tell shopkeepers on the sides of the road that my father was back and I was taking his orderly for a dip in the Ganges. The orderly was my “show and tell.”

On our way back home, we had gone only a short distance from the banks of the river when two British soldiers rode past us on their bikes. This was bait I could not refuse. Pedaling fast, I caught up with them.

Dressed in their civilian clothes, the soldiers were leisurely riding and talking to each other. They looked at me once and then ignored me. I could tell by their body language that they did not welcome me riding along beside them. I could pick up only a few stray words of their talk. But then, one of them wove the Hindi word “chootia” (asshole) into the conversation.

It was a commonly used word in the local vernacular, but it caught me by surprise that an Englishman would know that word. I grew up in a family where we did not utter such profanity, or the punishment would have been much worse than having your mouth washed out with soap. Until that day, I had never said that word.

Astonished, I looked up at them and asked, “You know ‘chootia?’”

Unfortunately, my first two words were drowned out, but the last word caught their attention. Immediately, I knew I was in trouble.

They stopped, ordered me down from my bike, and cornered me. One of them sternly asked me where my father was. Frozen with fear, I could not utter a word. My throat was as dry as desert sand.

Father’s orderly was some hundred yards behind and running towards us. When he caught up to us, the same soldier asked him in broken Hindi with the deep accent of an Englishman, “Are you his father?”

“No, I am his father’s ardaly,” he stammered, not quite knowing what was happening.

“Is his father an officer?” the British soldier inquired.

The orderly nodded his head, “Yes, Sir.”

“Tell the officer his son needs to learn manners,” the British soldier said.

The other soldier turned his face and moved a step away, as if he knew what was coming next and did not want to be a part of it. That, to me, was a warning of what was coming, but there was nothing I could do. The first soldier cocked his right hand as far back as he could, and with all his might he slapped my left cheek. The suddenness and force of it swung my head to the right and down to my shoulder.

For me, the world stopped at that moment.

It was not just another moment within the endless flow of time. I experienced eternity in that moment. My mind was clear, and I viewed the event as if from several feet above.

I can vividly recall the looks of those two British soldiers. The one who slapped me had a long face and wore round-rimmed glasses. His face was stern and cold, and his hair was combed straight back. The other soldier, who seemed to be younger, had a baby-round face and dark fluffy hair parted on the side, and he would flip his hair to the side with a toss of his head. He also looked to be the friendlier of the two. They were both wearing white, short-sleeved shirts. They were perhaps 18 to 20 years old—but, to a terror-stricken 7-year-old boy, they seemed like giants.

I can still see the faces of the 15 to 20 bystanders who had gathered around us in a semicircle. They are still standing there, unmoving and mute as statues. I can see the wince cross the face of the orderly when I was slapped, even though I was not looking at him at that moment.

I can read the mind of the child, the center of attention. Scared as he was, he had expected to be lectured. He expected to get a chance to explain himself, that he went to a British school and could speak English, that he had meant no offense. As was his nature, he would have made friends with the two soldiers and invited them to his house for a home-cooked meal. He expected to be treated as an officer’s son—certainly not to be slapped in public.

Upon being slapped, he expected immediate action from his protector, the orderly. He expected the orderly to use his lathi, a weapon that stayed frozen in his hands. He expected the surrounding crowd to curse the two British soldiers and beat them up unceremoniously. But neither the orderly nor the others in the crowd could lift a finger against them. Anyone trying to interfere would have been killed instantly, with impunity.

The boy felt shocked and disappointed when the British soldiers mounted their bikes and rode off, without even being confronted.

And then, the child actually got scolded by the orderly. It was obvious that the orderly’s manhood had been challenged and humiliated, and he was irritated at the child for being the cause of it. He threatened to inform the child’s father of the incident.

The rest of the way home, the child biked a few steps behind the orderly, as if in slow motion. Both were in a state of shame, and they could not face each other. They were experiencing the humiliation of helplessness—both personal and collective.

The slap had landed deeper than the child’s face. It had pierced the depth of his psyche.

For as long as I could remember, I had a sense that I was a visitor sent to live with my family temporarily. I felt that I was really from another family, another country. When I was four or five years old, I articulated that feeling to my mother. When she asked where my real home was, I told her, “England,” and that I would be returning there for good at the age of 10. Amused, she shared this with friends and relatives, and soon I was being asked to tell visitors about my “real home.” At first, I willingly participated. But, once I realized that I was being asked to perform, I stopped and refused to disclose any such feelings, even to my mother.

When the British soldier slapped me, it was as if I had expected him to know. He was one of the people I felt close to and with whom I identified. It was a peculiar feeling, as if one of “my own people” had humiliated me in front of these “others” with whom I didn’t really belong. Even more than that, it was as if I suddenly discovered how “my people” mistreated their hosts in their own land—hitting a child for a mere misunderstanding!

When the orderly was leaving with my father the next day, he took me aside at the railroad station and confided that he did not mention anything about the incident to my father. I was relieved. Compared to the British soldier who had slapped me publicly, I considered that poor, uneducated orderly to be much more civilized and cultured. It was clear that I did not want to grow up to be like the person who had slapped me.

With that one thunderous slap, I had grown up. I was no longer just a visitor in India. I was an Indian.

How dare a foreigner insult me in my own country?! I was not going to take it lying down. I was going to avenge it. The incident did not diminish my desire to go to England. It inflamed it. But, now I had to go there to avenge—to kill as many British as I possibly could. I would not be able to kill enough. But, symbolically, I would convey the message that my people were not as helpless as the bystanders around us that day had seemed. There was at last one brave person among them. “My people” and “I” had become one, and my revenge was intensely personal.

Over the next few years, the embers of my humiliation smoldered into anger. My every thought was like a gust of wind that fanned the flames into rage and hatred for the British.

That lasted until the evening of January 30, 1948, when Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated.

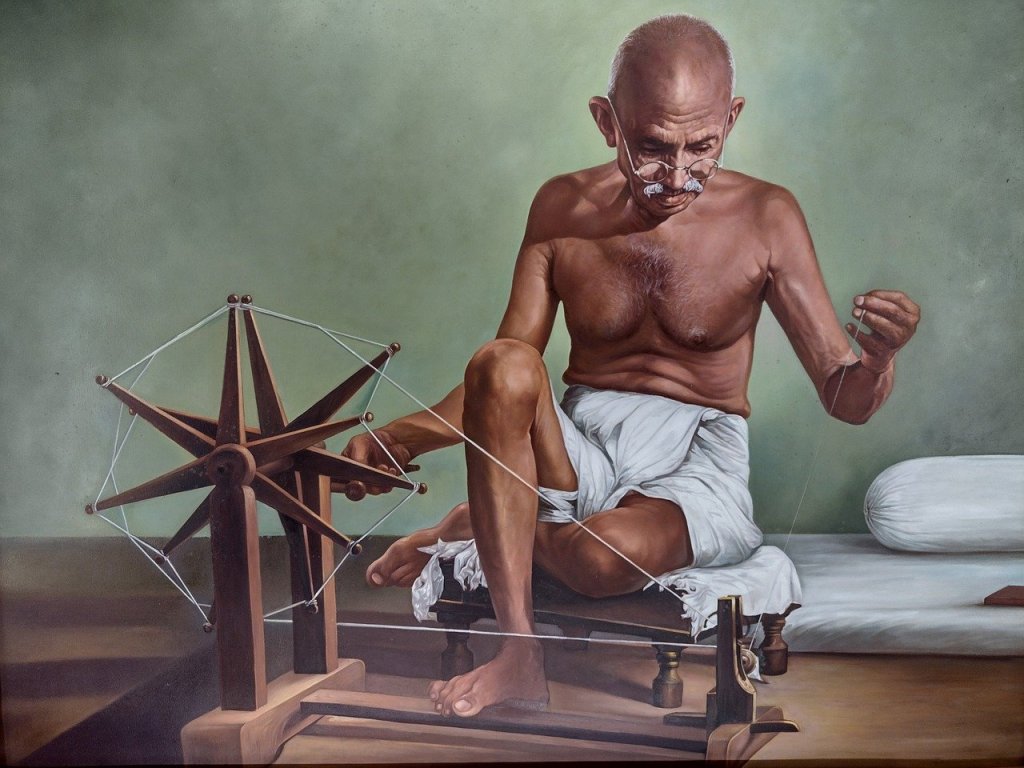

Gandhi’s nonviolent approach to driving the British out of the country had appealed to me as a child. At the age of six, I announced to my family that I was a follower of Gandhi. I even declared that I was only going to wear clothes made out of homespun Indian cloth, as Gandhi urged us to do instead of buying factory-made cloth from England.

Two years later, that one slap convinced me that the British would need to face the barrels of guns to be booted out. I became strongly opposed to Gandhi and his message of “turn the other cheek.” The only thing the British deserved was “an eye for an eye.”

I decided to change my psyche, which was quite gentle. I could not kill even a fly or a mosquito, and for that reason I had become a vegetarian at the age of four in a meat-eating family. But now, I had to learn how to kill. I made up my mind to learn to damage people. I tried to become a bully, to pick fights for no rhyme or reason.

I demanded that my parents take me out of the British school. My father was in the British army, but I insisted that, if I were to continue living in my family’s home, the tricolor Indian freedom flag would have to fly from our house—and it did.

Then, on January 30, 1948, when I was twelve years old, I heard the news that Gandhi had been gunned down. My heart swelled, and I started to cry uncontrollably, tears flowing over my cheeks. My emotion caught me completely by surprise. Stunned and confused, I had no idea why I was crying for someone I opposed.

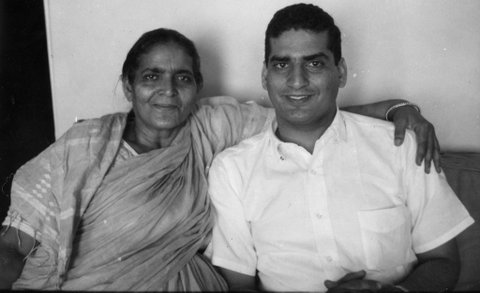

A large majority of India shed tears at the news of Gandhi’s death, but I wept all night long. My younger sister, ten-year-old Shakti, joined me, and we both sobbed as if our parents had died. Shakti and I were close, and I knew my sorrow alone was enough cause for her to cry.

The next morning, we saw the first rays of sun from our verandah, and at that moment we both stopped sobbing. It was as if the dancing sun rays had brought forth more than just a new day. For me, it turned out to be a new reality—a new life.

Over time, I realized that those drops on my cheeks were no ordinary tears. For me, they turned out to be like holy water that cleansed my psyche. It was a deeply spiritual experience that set me free. And, I had no need to hate the British anymore.

There is a legend in India that angels appear on the banks of the Ganges. I believe it, for it was there that those two British soldiers manifested themselves to awaken me. I thank them every single day.