October 1976

I woke up to a message.

For several minutes I sat with half-opened eyes, trying to comprehend the message. I got up and walked down the narrow aisle of the Boeing 747 en route from New Delhi to London. The hostess at the back of the plane checked her wristwatch and told me we were still three hours from landing.

Perhaps for the first time in my life, I was glad we were not yet at our destination. I needed time to process the newly-emerged thought.

While visiting my mother in Allahabad, India, I had seen a large tent city being constructed to host the Kumbh Mela, one of the most ancient Hindu religious festivals. Millions of Hindus gather every 12 years in Allahabad. For 40 days, throngs of people camp out on the banks of the Ganges River to worship or meditate many hours a day, visit various shrines, attend discourses by religious leaders, eat meagerly, and go for immersion in the holy river three times a day. Some people save their money for years in order to be able to attend the festival once in their lifetime.

Something—a voice—within me was urging me to go to Washington, D.C. and inform National Geographic magazine of this extraordinary event. But, no sooner had the idea emerged than the doubts kicked in: Most likely they already knew about it. After all, they are National Geographic! I would look like a fool.

I vaguely knew one person at the magazine, and what if he was not there or was busy and could not see me? Going to Washington without an appointment was risky. All I had to do was simply inform them in a letter from Wichita. If they had any questions, they could call me. Changing my schedule midway would be expensive. And my schedule was already loaded. Could I afford to crowd in one additional delay?

The idea was tender in its newness. But the doubts were strong and powerful, fully tested in prior battles—their long shadows like dark shrouds ready to smother the newborn idea. Like a baby, the fragile idea was holding tight to the only protection it knew—my trust in hunches from years of experience.

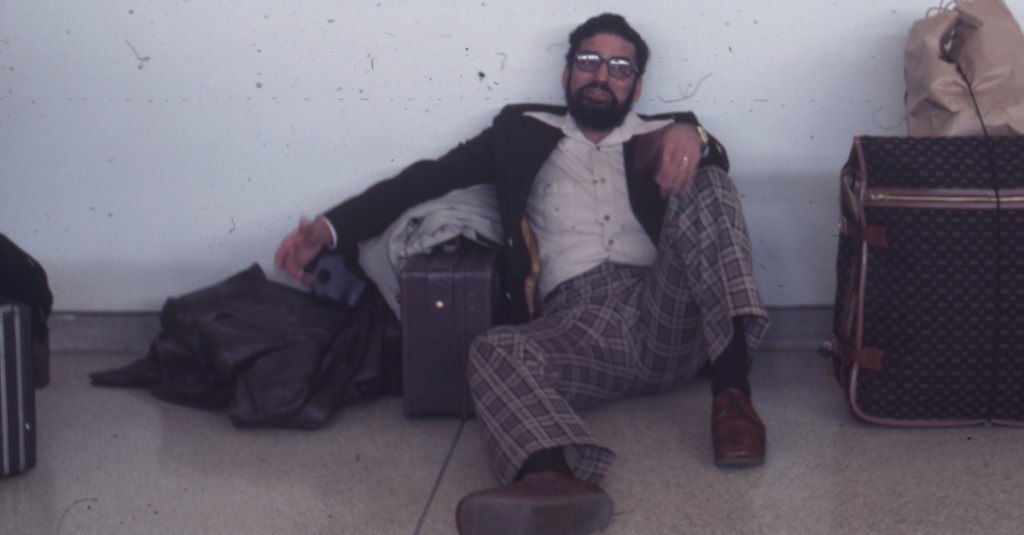

Just before landing, I made a decision. It would be like the toss of a coin. If it was meant to be, a schedule change would be feasible in London, and I would go on to Washington. Otherwise, I would continue to New York as scheduled.

The head was praying for New York, and the heart was rooting for Washington.

The heart won. The gentle lady at the Pan Am counter in London rerouted my flights through Washington and from there on to Wichita, where I lived. “Ah, the last seat!” she exclaimed victoriously. The die was cast, and I immediately felt relieved.

The next morning at 10:00, I was in the lobby of National Geographic asking to see Ken Weaver, the science editor. My heart was in my hands. As luck would have it, Mr. Weaver was in his office.

“I am the son-in-law of Everett Brown,” I told him over the lobby phone. “I met you a few years ago at McPherson College.” Silence. I felt my heart skip a beat. The wait seemed interminable. I realized that Mr. Weaver was trying to make the connection. After a long pause, he said he would come down to the lobby to meet me.

Ken was a third cousin of my father-in-law, and they had attended McPherson College together in Kansas. I had met him when my wife, Treva, and I had attended a dinner at one of my father-in-law’s class reunions.

Fortunately, Ken recognized me, apologized for not remembering, and invited me to his office. “What brings you to Washington?” he asked.

I told Ken I was just returning from my hometown of Allahabad, India. I told him about the tent city being constructed to host the Kumbh Mela, and that six million pilgrims were expected to attend. The sheer number was mind-boggling—a record crowd. I had simply come to inform National Geographic of the event, in case they wished to cover the story.

That was all.

“Tell me about it,” Ken said, putting his hands behind his head and leaning back in his chair.

As soon as I finished my story, he abruptly got up, asked me to wait a few minutes, and walked out of his office. Ken was gone for what seemed like a long time—long enough for me to browse through some books and magazines on his bookshelf.

When Ken returned, his excitement filled the office. He was almost out of breath. He tried to calm himself as he told me he had gone to see Mr. Grosvenor, the editor of the magazine. Ken wanted him to hear my story. It was a tremendous stroke of luck that Mr. Grosvenor could see me for a few minutes, he said. Mr. Grosvenor was busy for the rest of the day and then would be out of town for several days.

Ken gave me a quick briefing on Mr. Grosvenor as we rushed up to his office. He was the grandson of the founder of the magazine, and the great-grandson of Alexander Graham Bell. Ken urged me to repeat the story exactly as I had told it to him, right from the beginning.

We were asked to wait in his secretary’s office, because Grosvenor had asked three of his associates to join the meeting. Ken winked at me to indicate that was a good omen. Soon the others joined us, and we went into a large office. Grosvenor got up from behind his desk and came to greet us. He was much shorter and younger than I had imagined him. His handshake was firm. We all sat in chairs arranged in a circle away from his desk.

Grosvenor opened the meeting with introductions. There was the director of photography, the business manager, and a senior editor.

“Ken tells me you have an interesting story to tell us,” he began. “I am eager to hear it,” Grosvenor’s voice was commanding, and yet his eyes were gentle and smiling, as if to make me feel at ease.

I gave a thumbnail sketch of the historical background of the Kumbh Mela, but mainly focused on my personal experiences with the festival starting at the age of six. And then, I told of the last time I had attended.

“As college students, two of my friends and I attended the festival in 1954. We went simply out of curiosity; we were not spiritual pilgrims by any stretch of the imagination.

“Crowds were walking towards the Ganges at a leisurely pace. Most of the pilgrims were walking in small groups, chanting spiritual songs as they walked. The three of us were talking to each other, paying very little attention to our surroundings, when suddenly the crowd in front of us abruptly stopped moving.

“Before we knew it, the crowds at the back slammed into us. It was as if a car in front of us had stopped, and as we crashed into that car all the cars behind us slammed into us, causing a huge collision. Only in this case, it was not a multi-car pile-up, but a crush of human beings.

“Within seconds, the crowd locked in place, with not an inch of space to spare. Everyone was being squeezed as if in a vise. It was hard to breathe. Even though it was a cold day, all of us were perspiring.

“Suddenly, there was a movement—not of individuals, but of the entire crowd as one body. A block of several thousand people—male and female, young and old, rich and poor—were swaying as if they were one block of Jell-O on a plate.

“I felt like a grape trapped in that Jell-O. The movement was like a human earthquake. We three friends were shouting at each other, ‘Hold on tight!’ With terror in our eyes, we held on to each other for dear life, but our grips started to weaken. People were screaming at the top of their lungs, and it seemed as if one single voice was being directed at the skies. At that moment, we were united not only as one body and one voice, but also with one thought. None of us knew if we would come out of that black hole alive.

“After a few minutes, the crushing movement suddenly stopped, though we were still locked in place for a long time, perhaps an hour. I realized that in the brief time of the ‘human earthquake,’ we had experienced a glimpse of eternity, filled with the cries of men, women and children.

“Finally, the grip of the crowd broke, and we started to walk—like stunned zombies. After walking for a few minutes, we found out that, during the movement we had felt, several hundred people had been trampled to death and thousands more injured in a stampede. We three remained in that area for hours, consoling people who had lost friends and relatives. The stunned expression on the pockmarked face of one man will always remain with me—he had lost 28 members of his extended family.

“For days, we marveled at the thought that not one of us would have survived had we been a mere 100 yards ahead. Only a few steps separated life from death. We had witnessed the fragility and value of life.”

As I told this story, there was pin-drop silence in the room. I was experiencing something most unusual. After almost a quarter of a century, this was the first time I had been able to share that experience with anyone. Now, unrehearsed, the words flowed out from somewhere deep within me. I felt almost as if I were in two places at once—I was narrating the story, and yet at the same time I was in the audience, listening with rapt attention.

When the story was over, there was a moment of silence. Finally, Mr. Grosvenor spoke. “We were not aware of this event and had not planned to cover it. Would you like to go back and cover it for us?”

“Look,” I protested, “I simply came here to inform you of the event. I am not a writer. I have never written anything before.”

Grosvenor crossed his arms, his right-hand fingers caressing his left elbow. He looked straight at me, steadied his gaze for a moment, then with a brush of his hand dismissed my objection. “We have all the writers we want. Your job would be to tell the story like you have just told us.” He had made his decision.

I looked at the rest, and each of the faces was in support of what the boss had said.

The business manager, a burly man of good size, took charge in his deep, resonating voice. He reassured me that they had writers who would love to work with me. “It will be your article. They will help you polish it. You will have nothing to worry about.”

“As far as I am concerned, there could not be a bigger honor,” I said. “But I really came here only to make sure the event would be covered.”

“We understand that,” the business manager said. He then moved directly to the nuts and bolts of the assignment. When would I leave? How long would I stay at the festival? What would be my out-of-pocket expenses? I gave them an estimate, and it was approved on the spot.

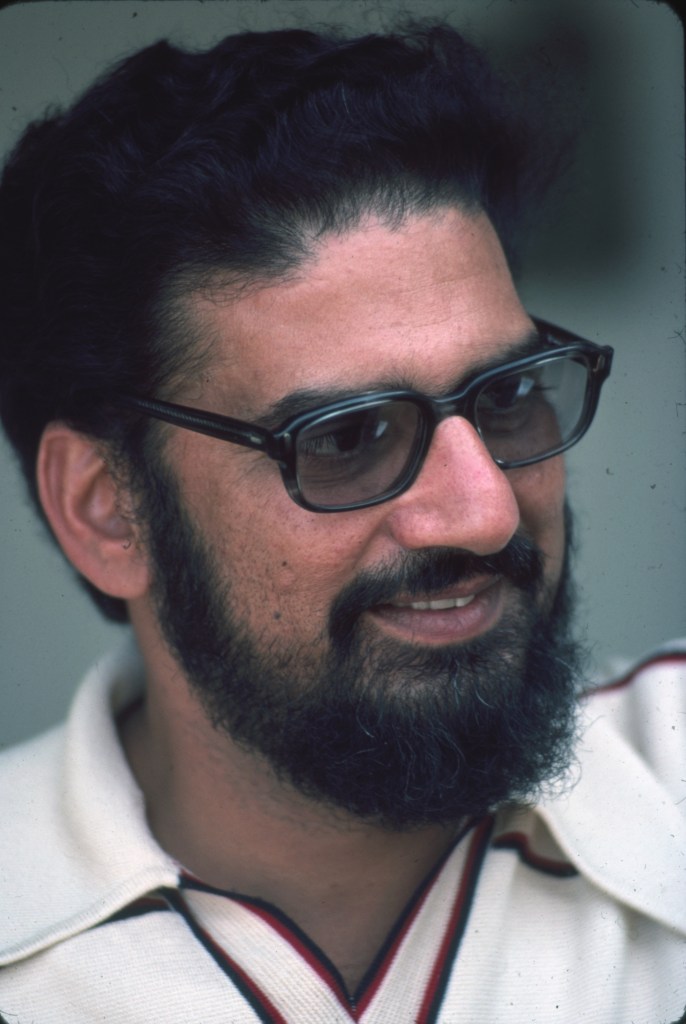

Grosvenor asked Robert Gilka, the director of photography, which photographer he might assign to cover this event. Gilka suggested Raghubir Singh, who happened to be in Paris at that time. “Wonderful,” Grosvenor approved.

Grosvenor then looked at the senior editor, who had been quiet up to this point, and said, “You will be working with him.”

She nodded and took charge: “National Geographic is very thorough about making sure all the facts are correct. At least two people will be checking all the facts you submit. Make sure you bring back any supporting documents that you can.”

“What type of supporting documents?” I inquired.

“Any press releases, newspaper articles, notes, names, dates, places, etc.”

I nodded my understanding and agreement.

Robert Gilka and Ken took me out for lunch. Gilka quizzed me about my photography interest and skills. He suggested that I take pictures also, independent of Raghubir Singh. Then I had the honor of receiving some tips on photography from Gilka—the maestro himself. He was a man of few words who could get straight to the heart of the matter.

Next I was taken to the executive viewing room, where the editor of photography, a gentleman from Egypt, was expecting me. He showed me some slides to demonstrate the elements of good photography. I was also loaned some specialized lenses for my Nikon camera.

I picked up my letter of assignment, and then I accepted Ken’s invitation to spend the night at his home and meet his wife, Modena. The next morning, I left for Wichita.

I had gone to National Geographic on a mere hunch, and I ended up being handed a major assignment to cover the Kumbh Mela. It seemed all the stars were in alignment. It was all so surreal.

Balbir, I just read your first story. I am moved by your willingness to listen to your heart and follow your “hunches.” I am grateful for this generous opportunity to hear and read your stories. You are giving a gift to all of us. Deanna

Very interesting a great read!

I remember you telling me this story, Balbir. What a great narrative!

By sharing this story you encourage us to Be and Act from our hearts. Gratitude for you and your story.

Blessings, Margalee

We love you, Balbir & Treva! Mom & I are reading a few of your stories today. Thank you for sharing your life & love with us all!! As a little girl, I remember you taught us Keedy Cousin Kids some songs & words from India. I always wondered what your home country was like. Love ya – Darcy & Nedra from Spirit Lake, Iowa

Loved the story. I now want to read the article you wrote for them

Balbirji, your very first story is already captivating! What are the odds of a young man from Allahabad walking down memory lane, wishing to share the incredible pilgrimage with the rest of the world, and becomes the lens of the story? You have always followed your heart and made a huge impact along with your wife, Treva. God bless you and your family for sharing these treasured stories.